This autobiography, like the author, is a work-in-progress; both are becoming more truthful and complete.

A “Manic Pixie Dream Girl” at midlife writing her own script

From the maternity ward window of the Good Samaritan Hospital in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, my nineteen-year-old mother would have looked out onto green hills whose roundness resembled her own belly. Deep below their tree-topped surface ran dark veins of hard coal that had fueled the growth of the Nation and the prosperity of our region for nearly two centuries. Not that any of this would have crossed my mother’s mind during the forty hours of labor she was enduring. When at last I emerged from her womb on a sweltering Sabbath afternoon in late-July 1977, most of the anthracite mines had been shuttered for more than two decades. All of the men in my Lithuanian and Polish grandfathers’ generation had toiled in the dark and dank of the mines. All of the men in my father’s generation were elsewhere underemployed.

Long before I was wailing in my mother’s arms at “Good Sam”, the coal barons had absconded the region with their riches—endowing the great cultural institutions of Philadelphia, New York, and beyond. In their wake, they left a land stripped not only of its minerals, but of its potential. The “resource curse” (so-called by economists and historians) would not so much be felt in the day to day living of the people of the Coal Region; we are nothing if not resourceful. Rather, the scourge of scarcity would fall upon our collective consciousness, hemming in our horizons and impoverishing our imaginations. And only imagination can break the curse.

In this barren landscape, I grew up with an overabundance—not of material wealth, or of love, but of neural synapses in my cerebral cortex. While other toddlers’ brains were efficiently shearing their unused neuronal connections in a natural developmental process called synaptic pruning, my own brain was apparently holding onto its infantile embarrassment of riches. My differences in cognition, perception, and affect are today called autism, ADHD, and giftedness—collectively, neurodivergence. Neurodivergent traits shape the lens through which I experience life as both sublimely beautiful and eminently difficult.

My mother logged my milestones in this “Catholic Baby Record”. She also passed on to me her Catholic faith and its sacramental optic that sees the miraculous in the mundane.

When chronically under-resourced, “giftedness” makes life at once too much and not enough. Growing up in a former coal company town during the 1980s and 90s felt bitter and sweet to me in a way that seemed never to arise to the consciousness of my peers. The tight-knit warp and weft of community and tradition nurtured and protected us, while the insularity and acculturated hopelessness of generations of exploited laborers served to stymie all of our growth. In the upstairs bedroom at my grandparents’ house where my mom and I slept after she and my father separated—and where she would sing Juice Newton’s “Angel of the Morning” to me as she left for her 4 a.m. nursing shift—I was already dreaming of wider horizons and growing impatient to seek them.

Not finding the beautiful worlds of my imagination among the towering culm banks and crumbling collieries of the coal fields, I discovered them in art, music, and literature and created them through writing, drawing, and painting. To bring beauty into my most intimate sphere, I decorated my childhood bedroom in our brand new mobile home at the edge of the wood in thrifted French Provincial style. My mother joked to the neighbors that her real child had been switched in the hospital nursery with a Vanderbilt baby, leaving her to raise one with “champagne tastes on nickel beer money”.

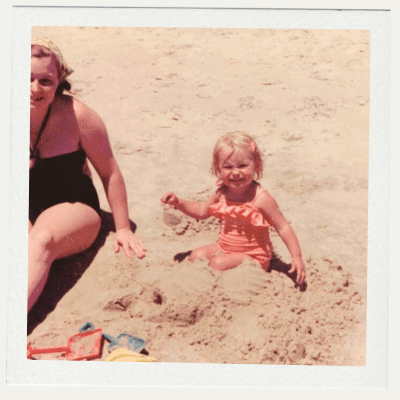

My parents were 19 when I was born and divorced under duress a year after this photo was taken. Their unlived life was a burden I would shoulder.

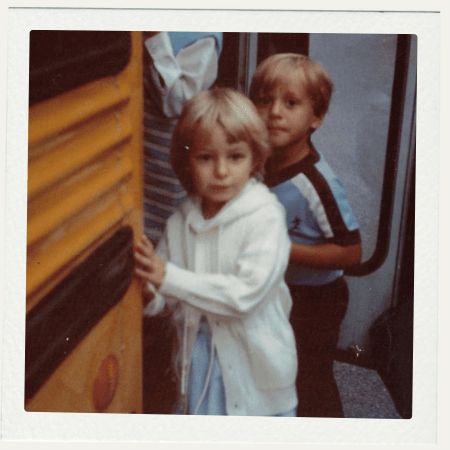

In my patch town of 350 souls, my precociousness endeared me to adults but unnerved other children. After my parents transferred me from the smaller Catholic parish school to the larger public one, the twenty-minute bus ride to school became a gauntlet of torture. Painting blue butterflies on my face, wearing leopard-print leggings and cat ears, and singing loudly with the bus radio to Madonna’s “Like a Prayer” made me an object of ridicule and a target for petty violence. I learned a lesson then that I would carry throughout life: express unbridled joy at your own peril.

Even as I dodged bullies on the school bus, I made cherished friends among other children in town. My childhood companions trusted me to guide them down abandoned mine shafts with stories of lost treasure. (We only discovered stashes of “girlie” magazines.) Together, we passed summer afternoons lazing on porch swings or lying on moss beds under red oaks and white pines contemplating God and the cosmos. This was our Garden of Eden, our time before The Fall, when no question was too big, no laughter too loud, no movement too spirited, no emotion too intense, no need for a mask. To these friends, I remain connected through time by a golden thread.

While waiting for the school bus in kindergarten, I was hit by a pickup truck, fracturing my pelvis in four places. When the adults asked what I was doing that I did not see the truck coming down the hill, I replied, “singing”.

With my best friend Mary Jane in NYC 2003: As of this writing, we’ve enjoyed almost forty years of friendship.

If home was a cage I could gild through boundless creativity and treasured friendships, school—where creativity is stifled in the name of conformity—was a prison I could not escape. Here, my neurodivergent traits were magnified and pathologized. In clinical terms, I exhibited monotropic hyperfixations, emotional dysregulation and delayed response, body dysmorphia, expressive dysphasia, delayed sleep phase, and demand avoidance—all of which made school a nightmare. In the elementary grades, I, the bullied, became a bully, victimizing an intellectually disabled child in the special education classroom where I myself belonged.

Throughout elementary and secondary school, my academic performance could best be summed up in a report card comment made by at least one teacher each year: “student not working to potential”. No experience illustrates this better than my first year in the fifth grade when my IQ tested at 143, yet I was held back for failing grades and “a lack of emotional maturity”. My mother’s pleas to my teachers that I be challenged more went unanswered. Thus began my slide down the gifted child to underperforming adult pipeline. Adults who earlier thought me destined for great things withdrew their support as they discovered their investment would not reap the rewards they expected. I felt a disappointment to everyone and very much on my own.

The sense that I was on my own and everything was up to me followed me beyond high school. Determined to leave the Coal Region behind, I took my diploma a term early and moved to New York City with an acceptance letter to the art school at Hunter College. For $100 a week, I rented a room in a rundown Victorian on Staten Island where my neighbors stole my mail and mice ate my ramen noodle packets. I had no idea how I would enroll in classes let alone pay my tuition. With no one to ask for help (no one back home had attended college), I postponed my enrollment indefinitely and instead worked in restaurants from Midtown to Downtown. My tips were consumed in clubs and bars all over Lower Manhattan—from the blue-lit grotto in Soho where I sipped Kir Royale beneath papier-mâché sea creatures hanging from the ceiling and at dive bars in the South Street Seaport where I smoked Players Navy Cut unfiltered cigarettes and downed Cutty Sark & soda with maudlin old mariners. My constant companion in these misadventures was my childhood friend, Jen, who had followed me from the Coal Region. After a year adrift and penniless, we both left New York.

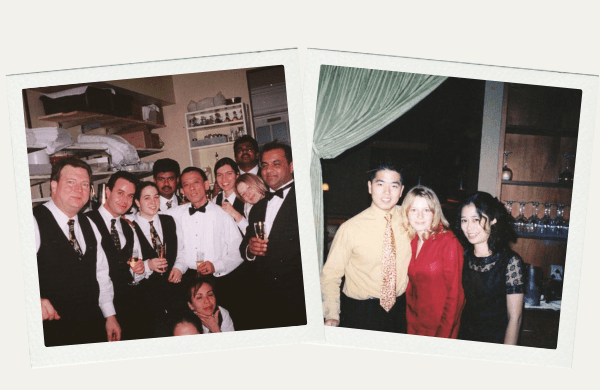

From New York, to Louisiana, to Philadelphia, restaurant work and restaurant workers were a saving grace.

From New York, to Louisiana, to Philadelphia, restaurant work and restaurant workers were a saving grace.

The next stop on my Grand Tour of aimless underachievement was Northwest Louisiana, where my stepbrother was stationed at an Air Force base and had invited me to live with him and his wife. What was to be a temporary hiatus until I could save enough money to return to New York, became a four-year sojourn during which I worked in “white linen” restaurants, making my way from shucking oysters at the back of the house to running the front in a Dior suit and heels. At 21, my restaurant manager’s salary enabled me to fulfill a longtime dream: inspired by literature, art, and the British indie pop music I so loved, I made two solo backpack trips around Scotland, Wales, and Northern England. I left a piece of myself on that island to which I will one day return to reclaim.

Following my second summer abroad in the UK, I returned to Northwest Louisiana, to my tiny clapboard cottage with the big magnolia in the yard. The filtered afternoon light in my front room reignited my passion for painting, and I made up my mind to attend art school in the Northeast. I was accepted at the selective Tyler School of Art of Temple University in Philadelphia. My tobacco-chewing, pickup truck driving, Dave Matthews Band loving, Cajun boyfriend drove me and my belongings north where I expected he would stay. He did not.

Of all the spectacular views of Edinburgh Castle, my 21-year-old-self thought the one from the car park best.

At Tyler, I was burning the candle at both ends and in the middle. With no funds to pay for school, I worked full-time during the day as a legal secretary in Center City Philadelphia and took classes by night. I struggled to meet Tyler’s credit requirements, which were more exacting than Temple’s other colleges. When I failed to file some financial form or other with the university by the appointed deadline, I had to sit out a semester. In my tiny apartment in West Philadelphia, where the mice no longer ate my ramen packets but the crotches out of my and my roommate Marena’s worn underwear in the wash basket, I fretted much over this failure. Little did I understand then about the ‘sparrows in the sky’ and the ‘lilies in the field’.

During this forced sabbatical, I chanced to watch a documentary on public television about Pope John Paul II. The Catholicism into which I had been baptized as an infant loomed large in my childhood. The only role religion played in my young adulthood, however, was when my Southern Baptist boyfriend broke up with me on the grounds that he could not be seriously involved with someone who, as a Catholic, was “not a Christian”. (What did I know at 21? He rode a motorcycle and looked after my cats while I was abroad. I thought he was sweet.)

Tyler School of Art c. 2000: I made mediocre charcoal renderings of sinks while listening to The Cure. The etiolated hair and complexion were part of my pseudo-Bauhaus vibe.

Learning in that documentary that my church was led by “a mystic” who was an actor and a poet—in other words, an artist—sparked something in my imagination. During this sabbatical, and in no insignificant amount psychic turmoil and confusion, I began reading the works of Franciscan monk turned Jungian psychoanalyst, Thomas Moore. The marriage of religion and depth psychology gave my struggle a framework of meaning that made sense in a way nothing had before. I have since turned to Jungian thought for guidance in navigating all of life’s crises.

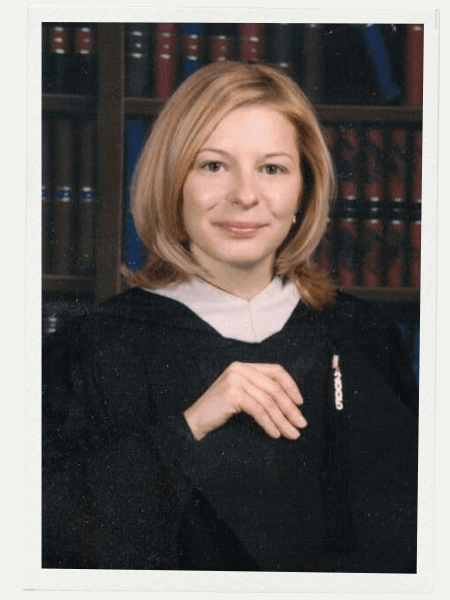

When I returned to Temple University the following semester, I enrolled in an Introduction to World Religions course. By the second week of class, I knew I would change majors and colleges, not least because I developed a crush on the grad student who taught the course —a Baltimore Catholic not much older than me writing a doctoral dissertation on Zen Buddhism. Without this limerence for my teacher, which was reciprocated though never realized, I doubt I would have gone on to become the star student of the Department of Religion earning a graduate degree and a teaching appointment there. Because my university studies were driven entirely by my own interests and passions, I thrived in a way I could not in elementary and secondary school.

Although “the Rachel” haircut might have you believe it’s 1995, I took my first degree in Religion at Temple University in 2005.

Near the end of my undergraduate term, a longing for a connection beyond my books emerged. Having read several spiritual memoir by women religious, I was discerning my own religious vocation. I trace the earliest whispers of this calling to childhood, being a favored pupil (and a source of consternation) to the nuns at my parish school who told my mother I was “an unusually prayerful child” because I spent much time in the prayer corner cradling the saint statuettes and thumbing through the Golden Book-styled hagiographies. (Rather than praying, I was isolating to self-soothe.) In my teens, I frequented two nearby rural religious orders with my mother—a convent of Discalced Carmelites and a monastery of Cistercian friars. The tranquility and simplicity I had known in these places and with these people would be unmatched anywhere else in my life.

When I told the tall, blonde bartender at the tony French restaurant on Philadelphia’s Main Line where I was hostess my plans to take vows after graduation, he scoffed: “you’re too pretty to be a nun”. Because he had many more years of formal Catholic education than I, and because I thought he was cute, I believed him. When I informed my extroverted best friend Mary Jane of my plans, she said pointedly: “Girl, you need to start dating.” At that point, I had been five years celibate, the rejection sensitive dysphoria and sensory overload of autism making relationships and sexuality especially fraught.

So when a handsome, middle-aged man I had met at a friend’s Valentine’s Day party asked me to go for coffee, I heeded Mary Jane’s dictum and accepted the invitation. Matt was 45, and I was 27. He was youthful and fit, being a triathlete who had the summer before ridden behind the peloton in the Tour de France. More importantly, though we didn’t have a word for it yet, we both spoke the same language: autism. I could communicate with Matt with an intuitive ease I had never approached with any other (heterosexual) male person.

Despite never “falling in love”, Matt and I married five years later. We had both felt led astray in the past by euphoric romantic projections, and we considered the absence of such projection in our relationship augured well for its stability and sustainability. Following our Philadelphia wedding, we moved to Matt’s hometown of Reading, Pennsylvania, where Matt, an inveterate gardener, cultivated a woodland garden sanctuary surrounding our suburban home. The companionable affection that developed between us over twenty years provided a bounty of cherished memories and sacred lessons.

“I am for you and you are for me, not only for our own sake, but for others’ sakes.” I included this verse from Whitman’s delicious poem, “A Woman Waits for Me”, in the printed program for the Nuptial Mass to affirm this marriage would be a means of expansion.

A chapter of life in which I was well supported by marriage to Matt, someone who could easily see through the prevarications and machinations of a dysfunctional family, was when I met my biological father as an adult. Although my father lived only ten miles away while I was growing up, I did not see him from the age of three until 33. Following their divorce, my parents’ joint shame ensured that during my most formative years, I had no relationship with the family member I most resembled.

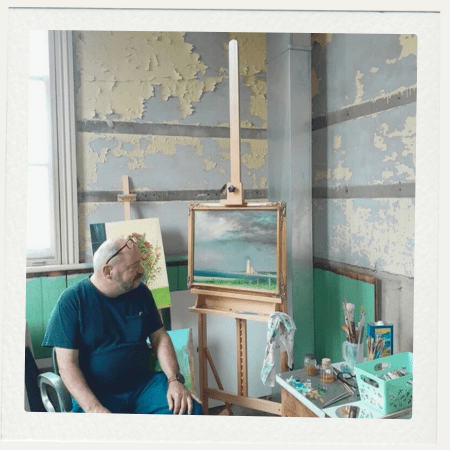

Meeting my father in my thirties was the missing piece in the puzzle of understanding my personality, which was distinct from everyone else in my family. “Larry” is a person of varied interests and talents: landscape painting, photography, model-ship building, astronomy, general gadgetry. Owing to undiagnosed ADHD and most likely dyslexia, he dropped out of high school and worked as a cook for most of his life. Because he decorated his apartment with antiques and remained a bachelor, his neighbors considered him eccentric and assumed he was gay.

My father in his studio

Rather than a bachelordom borne of queerness, however, my father may have been awaiting the return of my mother. And my mother—though she remarried and loved my stepfather, Joe, and grieved bitterly when he was killed in a car accident in 2004—may have been awaiting the return of my father. The life force that drew Larry and Diana together at the football stadium of Tamaqua High School during the Summer of 1976 had not diminished in the intervening decades. Now that force, which flows like water, would reunite them by the path of least resistance: I would be the conduit. Through their relationship with me, my parents reestablished a relationship with each other thirty years after their bitter divorce and estrangement.

After finding each other again, my folks also discovered their individual purpose. My mother skillfully leads the local historical society, and my father occasionally wins awards for his paintings and photographs (while also helping my mom with her considerable community work). In being released from the grip of my parents’ unlived life, I’ve been set free to live my own. In 2016, I founded HENNY FAIRE Co., a thriving perfumery where I offer my own olfactory art and bespoke fragrances in the kind of charming boutique about which I daydreamed while writing my undergraduate papers. While I still keep one foot in academia as an adjunct and through continuing education, I can now separate my self-worth from my academic achievements and hold my aesthetic and intellectual pursuits in tandem.

Nowadays, I prance around my boutique pretending to spray perfume for Instagram.

Midlife has proved a reckoning with my own unlived life, a time of regretting the “choices” I made compelled by a need for safety rather than a desire for life. Unactualized talents and passions have a way of drawing psychic energy unaware like background apps running on a phone using up memory and depleting the battery. Midlife has been a period of grief and recognition of a protracted exhaustion.

I once heard someone say, “being autistic is like always being in a midlife crisis.” Being autistic and in a midlife crisis has therefore been its own special hell. The word autism means “state of self” and refers to an orientation wherein the individual is naturally drawn inward. The introversion that attends midlife has felt like a tsunami—with my inner world pulling me under the waves, while the demands of the outer world buffet and break me like driftwood.

In recent months, however, I see a glimmer of sunlight at the crest of the waves, perhaps even a glimpse of a shoreline in the distance. I’m learning that when I trust my neurodivergent processes, I can trust myself. My “operating system” will never function like that of most people; however, it does function. My neurology has conditions and logic of its own that when honored, rather than resisted, make me capable of things most others are not.

Along with trusting neurodivergent processes, I’ve learned to turn to fellow neurodivergent people for the mirroring and support that have eluded me most of my life. Conventional social interactions have always drained my life force; soul connections with fellow neurodivergents fuel it. These connections need not endure through time to have this palliative and nourishing effect. Indeed, solitude is where I come to life in the most vibrant colors. The world of imagination and the life of the mind will always be my natural home. Today, I’m consciously creating an expansive, autonomous life that accommodates my dual needs for solitude and soul connection.

Stepping into an expansive new life has not been without sacrifice. Most notably, I determined that my marriage was incompatible with the Self that is emerging, the person I am becoming (and truly, always was). I can write a great deal about the protracted and painful process of growing apart that Matt and I endured, especially in the two years after I entered menopause. One day, I may also write about how we managed to separate, not only amicably, but with compassion, forbearance, and forgiveness. Here, I’ll suffice to say that the marriage revealed itself lacking in two vital qualities: 1) a Friendship in which we both see and value the same truths, and 2) Eros, or, passionate love. While absence of the latter once conferred a sense of safety that may have felt necessary earlier—that is, the boys and men whom I might have loved passionately in my youth felt too dangerous (as well as fascinating) for their apparent resemblance to my absent father—I came to see the lack of passion in my marriage not only as a denial of joy but as an impediment to spiritual growth. For a neurodivergent person, passion is fuel, without which we cannot begin to undertake the work of relationship nor the task of becoming who we are.

At middle age, the vision of life and faith I’m embracing can best be illustrated by a story I heard a Capuchin father tell from the pulpit of St. John the Evangelist Church, the parish in Philadelphia’s “Gayborhood” where I attended mass as a student. Speaking figuratively, the father told the tale of a poor soul who had just died and arrived at the Gates of Heaven. As the soul met God, he prepared to rehearse all of his sins and to confess how sorry he was for them. But God stopped him. “I have only one question for you”, and this, the Capuchin paused to inform us, God asked with a twinkle in His eye…

“Did you enjoy my Creation?”

Add artworks here